This website uses cookies for a variety of purposes including to help improve our website, and for other reasons as set out in our privacy policy. By using our website, you acknowledge and consent to the use of essential and analytics cookies, as described in our Cookie Policy. To understand more about how we use cookies or to change your preference and browser settings, please see our Cookie Policy.

Jennifer Chambers | Senior Analyst, Medical Analytics | July 2024

Article summary:

- Vaping is generally considered less harmful than smoking, however longer-term risks have not had time to emerge and could prove considerable. The habit is certainly not without risk.

- Vaping presents complex health risks, primarily relating to the chemicals inhaled by users. Some relatively modest acute risks exist, but of greater concern are theoretical links to future diseases, including cancers.

- International public policy on vaping as a smoking cessation aid varies a great deal. Some countries encourage usage while others are choosing to ban some or all kinds of e-cigarette, which may limit future vaper populations.

Who is classed as a smoker?

Most people would define a smoker as someone who inhales smoke from burning tobacco, usually, but not exclusively, in the form of cigarettes. For insurers, the usual definition of a smoker is anyone who has used any tobacco or nicotine-containing product over the last 12 months. This includes e-cigarettes, chewing tobacco and nicotine replacement products such as gums, patches and inhalers used to aid smoking cessation, a fact our end consumers may be surprised to learn.

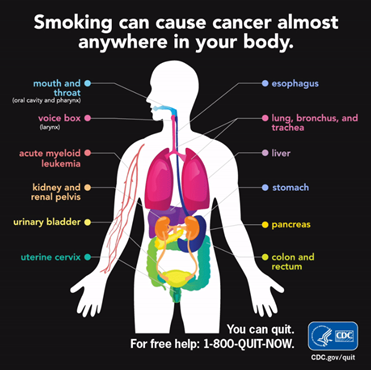

Smokers pay substantially larger premiums for their life and health policies in any market which differentiates by smoking risk. This is due to their increased risk of disease and early death when compared with non-smokers. Smoking tobacco has been known to cause lung cancer for over 70 years, and it is now associated with a wide range of other cancers. It has also been proven to cause cardiovascular and lung disease, and has been linked with type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis amongst other conditions.

As a result of these known health implications, a smoker’s life insurance premium could be up to around double that of a non-smoker. This reflects the fact smokers have twice the mortality of non-smokers.[1]

However, smoker rates are based on the known health impacts of traditional tobacco smoking, with no separation or blending of rates for those who solely use e-cigarette style devices, also known as vapes, and other non-cigarette alternatives. This is partly because their relatively recent introduction means that we have little long-term data on which to model vaping risk to health, and partly because international studies indicate that vapers, particularly those aged 20 and under, are three times more likely to later take up smoking tobacco products than non-vapers.[2]

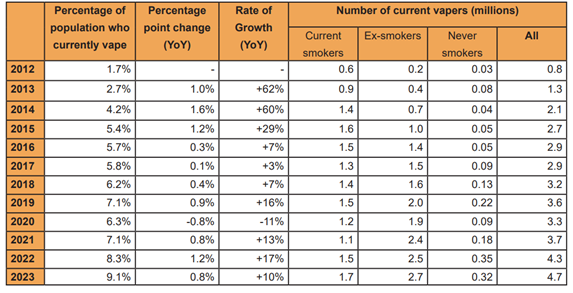

Despite this, many public health bodies and anti-smoking charities worldwide assert that the use of e-cigarettes and similar alternatives are significantly less harmful than smoking. In markets where this discrepancy exists, inconsistent messaging at least risks confusing those who vape, and insurance outcomes could even be perceived as unfair. In 2021, approximately 3.2% of US adults and 4.9% of UK adults exclusively vaped[3] [4] (i.e. they did not also smoke normal cigarettes). This proportion is steadily growing, as exemplified in the table below, documenting the rising number of British e-cigarette users. As such, vapers represent a relatively large potential market should more competitively priced life and morbidity products become available. Would such products be feasible from a risk perspective?

[3] Products - Data Briefs - Number 475 - July 2023 (cdc.gov)

[4] Use-of-e-cigarettes-among-adults-in-Great-Britain-2023.pdf (ash.org.uk)

Smoking alternatives - the ‘ENDS’ of cigarettes?

Nicotine is a highly addictive chemical found naturally in the leaf of the tobacco plant. Smoking tobacco can lead to both physical and emotional dependence, making the habit incredibly hard to quit. Nicotine replacement therapy products such as gums and patches have been around since the 1980s. Their usage is widespread and they are safe. These products have proven effective in reducing nicotine withdrawal symptoms and cigarette cravings, yet relapse is common due to early discontinuation. With the exception of inhaler-type devices, these methods of nicotine replacement don’t counteract the powerful psychological ‘hand-to-mouth’ habit of smoking.

Since they were first developed in the early 2000s, a variety of artificial cigarettes known as Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) have hit the market. These products are more usually referred to as electronic cigarettes (also e-cigarettes and e-cigs), vapes, vape pens or mods, and the action of using them is often called ‘vaping’ or ‘Juuling’ after one of the newer pod-style vape brands. These devices promise the same smoking sensation, including a similar look and feel, but without tobacco.

Although the newer generation vapes may look different, they all work along the same general principle. Essentially, these battery-operated devices heat up a metal coil to between 190-235°C (374-455°F) which vaporises nicotine-containing liquid (‘e-liquid’ or ‘juice’) contained in the cartridge. The user can then inhale the atomised liquid through the mouthpiece mimicking the draw of a regular, combustible cigarette. The e-liquid is based on a mix of water, alcohol and two humectants, propylene glycol and glycerol or vegetable glycerin, which can be mixed in different ratios according to the desired vapour levels. They often contain flavourings (candy, fruit or menthol flavours are popular) and are sometimes also coloured with food dyes. In some instances, vaping liquids may contain the cannabis-derived chemicals cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) although the majority contain nicotine, the strength of which varies by product. Nicotine-free e-liquids are available although less common.

Another type of cigarette replacement product beginning to gain popularity are ‘Heat not Burn’ (HNB) or ‘heated tobacco product’ (HTP) devices, which can be likened to a cross between a regular, tobacco cigarette and an e-cigarette. Manufactured by tobacco companies, the HNB/HTP devices use a battery to heat an internal metal core which is surrounded by tobacco. Cigarettes burn at around 900°C (1650°F) whereas HNB/HTP devices heat the tobacco to approximately 350°C (662°F) whereby a vapour is produced rather than smoke. Heated tobacco products occupy a relatively small market share in the UK and USA, with an estimated 1.7% of UK adults having tried these products.[1] However, these products are increasingly popular in Japan and where nearly 11% of adults regularly use them.[2]

Comparing e-cigarettes and traditional smoking

Smoking tobacco releases thousands of chemicals, approximately 100 of which are known or suspected to cause cancer, including tar. The WHO consider all forms of tobacco to be harmful to human health, with no safe exposure limit.

HNB/HTP devices are marketed as contributing to ‘tobacco harm reduction’ by emitting lower concentrations of harmful chemicals by heating tobacco instead of burning it. Although most data is linked to the tobacco companies, some independent research exists to support these claims. IQOS brand devices yielded nearly half the amount of tar, one-hundredth the level of carbon monoxide and lower concentrations of tobacco-specific nitrosamines[3] with their manufacturer Philip Morris International citing them as emitting ‘95% lower levels’ of chemicals than cigarettes, a remarkably similar statistic to that from Public Health England regarding vape safety (see below). Whilst this may indicate some advantage, it very likely does not equate with them being 95% safer and the health ‘benefits’ (relative to traditional smoking), are currently unknown. As these devices contain tobacco, it is likely that they still confer a significant risk to health. Further, there is no evidence that these products are useful as smoking cessation aids.

The use of e-cigarettes is much higher than the use of HNBs/HTPs. Manufacturers claim that vaping is a safer alternative to smoking because e-cigarettes don’t contain tobacco, and so users will not be inhaling tar and other dangerous chemicals such as carbon monoxide which are known to be contained in cigarette smoke. It is claimed that by replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes, smokers can prevent further health damage as well as improve heart and lung function whilst eliminating nicotine withdrawal symptoms. It is also claimed that e-cigarette vapour is less harmful for bystanders and that it doesn’t have a lingering odour. A report from Public Health England in 2015 estimated that vaping is 95% safer than smoking, with the remaining 5% risk viewed as a “cautious estimate” for unknown long-term effects of inhaling e-liquid additives such as flavourings.[4]

This estimate proved controversial and the current body of evidence does not allow us to state with any confidence that the long-term risks posed by e-cigarettes truly are as dramatically lower than traditional smoking as stated.

Across the world, many other public health bodies and charities also support that vaping is less harmful than smoking, a broader claim which is easier to support, although most still have serious concerns regarding its long-term safety. Most acknowledge that vaping is not without risk and therefore should not be recommended for non-smokers. So what are the potential health risks of vaping?

Health risks of e-cigarettes

E-cigarette vapour might not contain tobacco, but they potentially expose users to a variety of other chemicals, which may prove harmful. Whilst e-liquid is mostly comprised of humectants, solvents, flavourings and colourings that are approved for use in food, vaporising the liquid may create altered chemicals that have never been tested for inhalation safety. Examples of this include propylene glycol which may cause asthma when vaporised, and relatively common ingredients such as the sweetener sucralose and flavourings like vanilla bean extract and cinnamon which may break down into toxic or cancer-causing chemicals when subjected to high temperatures.[5] The metal coils which create the aerosol may impart toxic metals and small, ultrafine particles to the vapour as they degrade, whilst the traces of a chemical used in pesticides and disinfectants have been found in some vape liquids which may result in cyanide formation after heating. Counterfeit vape liquids may be laced with additives to decrease production cost.

[1] Smokeless tobacco: 5 common questions about ‘heat not burn’ products answered (cancerresearchuk.org)

[3] en (jst.go.jp)

[4] McNeill-Hajek_report_authors_note_on_evidence_for_95_estimate.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[5] What is in a vape? Everything you need to know (nbcnews.com)

Short-term health impacts

The chemicals found in e-cigarette vapour have been implicated in causing lung damage and even death. In 2019, there were over 2800 non-fatal and 60 fatal cases of e-cigarette or vaping associated lung injury (known as EVALI) across the USA, where patients exhibited serious lung impairment. Research found that the majority of cases were linked with inhalation of vitamin E acetate, added as a cheaper constituent in counterfeit cannabis-derived THC-containing vape liquids.[1] Previous medical history including pre-existing heart and lung conditions, obesity and increased age were more common in fatal cases. Although the possibility of other contributing factors from regular nicotine vapes could not be fully excluded, the likelihood of EVALI affecting users of regular e-cigarettes is relatively low. In the UK, only one death has been reported due to EVALI, yet as of January 2020, 244 vaping-linked adverse event cases including 4 deaths had been reported through the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) yellow card scheme.[2] This represents a very small proportion of UK vapers, which stood at around 3 million in the same year.

The use of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes has also been linked with seizures. Nicotine poisoning can result in seizures, convulsions and brain damage. Whilst the nicotine content of e-cigarettes is increasingly regulated and is often comparable to combustible cigarettes, counterfeit and illegal products, user inhalation methods and increased vaping owing to addiction could increase the risk of nicotine poisoning. The risk appears to be higher in younger adults and children as over two thirds of the 250 seizure cases reported to the US FDA in 2021 occurred in adolescents and young adults.[3] While this partly reflects the demographic most likely to engage with these products, it may also be due to ongoing brain development in these age groups.

Lastly, among acute impacts, reports of injuries due to exploding e-cigarettes exist but are rare in comparison with fires and injuries caused by cigarettes and smoking.[4] In these instances, burns, house fires and injuries usually resulted from failing batteries or incorrect device charging.

Long-term health impacts: the big unknown

At present we can say more about short-term effects of these products on health than long-term ones. So far, durations of device use are too short to provide good insight into long-term consequences. Nonetheless, many researchers believe the type and number of chemicals inhaled imply significant risk of long-term diseases, including many typically associated with traditional smoking.

Recently, scientists found that the DNA from the mouths of both smokers and e-cigarette users had similar changes.[5] The type of changes help control which genes are switched on and off, and several have been found to occur in lung cancer. However, these type of DNA changes are potentially reversible and no causal association was examined. Further studies are required to confirm these findings and to understand if and how the changes might impact health.

More broadly, scientists analysing typical e-cigarette chemicals believe the habit is likely linked to a broad range of medical conditions, which will be familiar to those who understand the risks of typical smoking. Medical consequences could include myocardial ischaemia, hypertension, tachycardia, endothelial dysfunction and stiff arteries, which might reasonably be expected to lead to circulatory outcomes including heart attacks and strokes.[6] E-cigarettes could also cause oxidative stress likely leading to cancer-causing processes driven by ‘free radicals’, using some of the same mechanisms through which too much sun or alcohol can cause cancer.[7] Demonstrating risk in a laboratory is not the same as proving and quantifying actual health risks. A key unknown is whether typical quantities consumed make these frightening endpoints just as likely for vapers as for smokers and, if they are less likely, by how much.

Conflicting legislation

In spite of these risks, UK officials are largely in favour of e-cigarettes, exemplified by the National Health Service welcoming vaping as a recommended method for quitting smoking. Although vapes are not approved for provision under prescription, the UK Department of Health and Social Care announcing last year that nearly 1 in 5 smokers would be offered a free e-cigarette starter kit as part of their ‘swap to stop’ campaign. However, all four UK governments have voted to ban disposable vapes in 2025 to discourage youth vaping and limit environmental impact, following similar legislation already in place or being introduced in other countries, including Australia, the USA and France.

Elsewhere, opinions on vaping are often far less positive, particularly with regards to disposable e-cigarettes. In the USA, the FDA still does not recommend e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid, whilst in 2020 the US government moved to ban most flavoured vapes and raised the legal age to purchase these products to 21. Since 2022, the FDA and vape brand Juul have been in dispute over a potential ban due to concerns over toxicology data. Australia moved to ban nicotine-containing vapes except where they are prescribed as a pharmaceutical product and, as of this year, it has become illegal to import into the country any vapes not approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration. The use, possession and sale of e-cigarettes is illegal in Thailand and Singapore, whilst selling nicotine-containing e-cigarette products is prohibited in Japan.

Insurance impacts

Insurers are understandably keen to understand whether they could or should treat users of this technology differently from typical smokers and, if so, in what ways. These decisions require data which is frustratingly slow to emerge.

E-cigarette devices and liquids are relatively new, with little data so far on the effects of vaping over extended periods of time. The changing landscape of e-cigarette usage, research and legislation also makes it harder for insurers to become comfortable with the level of risk posed by vaping. Although we discuss in this article relatively small short-term risks associated with vaping, the bigger question relates to longer-term risks. What health outcomes will be associated with long-term vaping? Will these vary by product? Are there relatively safe lower levels of usage? And, crucially, how does all of this compare to traditional smoking?

The available data does suggest vaping will likely prove less harmful than cigarettes over the longer term, which would in theory support the creation of a reduced rate for a specific subset of smokers, but the extent of this reduced risk remains in considerable doubt. Note that in some markets, especially in Asia, rates do not differentiate by smoker status at all, meaning adopting vaper rates would require even more fundamental change, for which market appetite may not exist.

Certainly many emerging studies suggest vaping is not ‘safe’, when compared with not vaping or smoking. Plausible links to future conditions like cancer exist in laboratory studies and, while we ignore these at our peril, definitive data could take many years to emerge.

Insurers will also want to understand risks associated with transitions between habits, for example from traditional smoking to vaping. Risks associated with many cumulative years of smoking will take time to dissipate and, especially in those who smoked for a long time, may never fully disappear. Even when data does emerge, typical underwriting journeys perform only a point-in-time assessment of current smoking habits and in their current form cannot be expected to provide rich data about past habits. These uncertainties make adaptations to rates complex even when better data exists.

Conclusion

Legislative trends around the world remain towards strongly discouraging use of, and perhaps even restricting access to, traditional cigarettes. Canada aims to reduce smoking prevalence to 5% by 2035 and recently became the first country to rule health warnings should be printed on individual cigarettes. The UK recently passed legislation designed to ban the sale of cigarettes to anyone born in 2009 or later, though similar legislation in New Zealand was reversed following a change of government. The impacts of these moves on usage of both traditional smoking and vaping habits remains to be seen.

The greatest risk of vaping is most likely the inhalation of unknown chemicals. Increased legislation to limit illegal, poor quality or counterfeit vaping products could mitigate some health concerns over toxic additives in e-liquids. However, moves in some markets to tax vape products according to nicotine levels could promote users opting to vape cheaper, lower nicotine products more often to feel the same effect, increasing their exposure to vape additives and chemicals.[8]

Although the direct health impacts of vaping appear to be evident so far in only small subsets of vapers, it is likely that due to the short history of e-cigarette usage we have not reached the full limit of adverse effects. It is highly likely that vaping is more harmful to health than not vaping. After all, smoking tobacco was once thought to be beneficial to health.

[1] Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products | CDC Archive

[2] Jan-2020-PDF-final.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[3] Three Seizures Provoked by E-cigarette Use in a Five-Year Period: A Case Report - PMC (nih.gov)

[4] How likely is your e-cigarette to explode? - BBC News

[5] Can vaping cause changes in our cells? (cancerresearchuk.org)

[6] Electronic Cigarette Use and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases - PMC (nih.gov)

[8] New high nicotine vaping tax could drive riskier habits | London South Bank University (lsbu.ac.uk)

Jennifer Chambers

Senior Analyst | Medical Analytics

Discover more Vital Insights

Protection

Changing regulations an area of opportunity for reinsurers

When asked what opportunities life reinsurers in Asia have, Pacific Life Re's Vasan Errakiah was quick to cite demand for insurance, changing regulations and the adoption of new technologies.

.png)

Protection

Solving the implementation puzzle of machine learning

Asia Insurance Review spoke to Pacific Life Re's Mr Ong Qian Hao and FWD Group's Ms Fiona Hermans to understand how strategic partnerships can effectively address these challenges and lead to successful outcomes.

Medical Advances

Update on COVID-19 and Long Covid

Read our update on the impact of mortality from COVID-19.

Medical Advances

Lung cancer screening, marginal gains or a game changer?

Lung cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage leading to poor prognosis for the individual. We look at how screening could have an impact.

Underwriting & Claims

From Barrier to Benefit: Rethinking the Future of Underwriting

Underwriting has been going through significant transformation over the last few years and continues to accelerate at an unprecedented pace. Traditionally seen as a barrier, there is now a growing opportunity to position underwriting as a strategic asset.

Protection

Leveraging big data insights in reinsurance

Big data analytics has been instrumental for (re)insurers aiming to boost performance, efficiency, and effectiveness.

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 2

From emerging drugs which battle obesity to a review of the effectiveness of new blood tests both to detect cancer and to help slow down Alzheimer’s, we hope these insights help keep you up to date with the latest in medical research.

Medical Advances

Vaping vs. smoking: what are the risks?

Vaping is generally considered less harmful than smoking, however longer-term risks have not had time to emerge and could prove considerable.

Medical Advances

Gut Check: the concerning rise of bowel cancer among young adults

Despite broadly improving cancer mortality, some types of the disease are increasing in incidence

Protection

Serving the Underserved

Consumer Duty has put increased focus on how much value different customers get from financial products. But how well is the protection industry serving different customer groups? Who are the most underserved groups, and what can the industry do to help serve these groups better?

Underwriting & Claims

The future of underwriting is now... are we ready?

Underwriting processes, practices and philosophies are changing with faster pace than we have ever experienced before.

Medical Advances

Tackling the obesity crisis

A new generation of drugs has now well and truly arrived aiming to improve weight loss. The drugs are heavily touted by celebrities and influencers, despite many of them having no medical need to lose weight. Obesity contributes significantly to some of the most common causes of death including heart disease and cancer, as well as affecting quality of life for millions. In this article we look at these increasingly available drugs offering hope to more people with obesity. We consider their potential to broadly improve health, and their limitations.

Medical Advances

New drug may slow down multiple sclerosis

Scientists successfully conducted early-stage trials which provide hope of a future cure for some of the most severe types of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Medical Advances

Exploring the latest medical advances in cancer detection

The world’s largest conference dedicated to the science and treatment of cancer took place in Chicago in early June. The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting is a popular forum at which new scientific developments are often revealed.

Medical Advances

Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumour (PitNET)

A recent review by WHO resulted in reclassification of pituitary adenoma as described in the article

Medical Advances

Climate change and its impact on mortality and morbidity

In 2023 we’ve seen soaring temperatures across the globe along with devastating storms and wildfires. Why is our climate changing and what impact is it having?

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 1

Welcome to our first edition of Vital Insights. Here we’ve put together a collection of articles covering some of the major issues of the day with a specific focus on how they will impact mortality and morbidity.

Medical Advances

Deep dive: Alzheimer's

Total deaths from dementias in high-income countries have almost quadrupled in the last 20 years, yet so far medical science has very few answers. This article looks at the recent emergence of the first drugs which may be able to modify the effects of this terrifying disease

Medical Advances

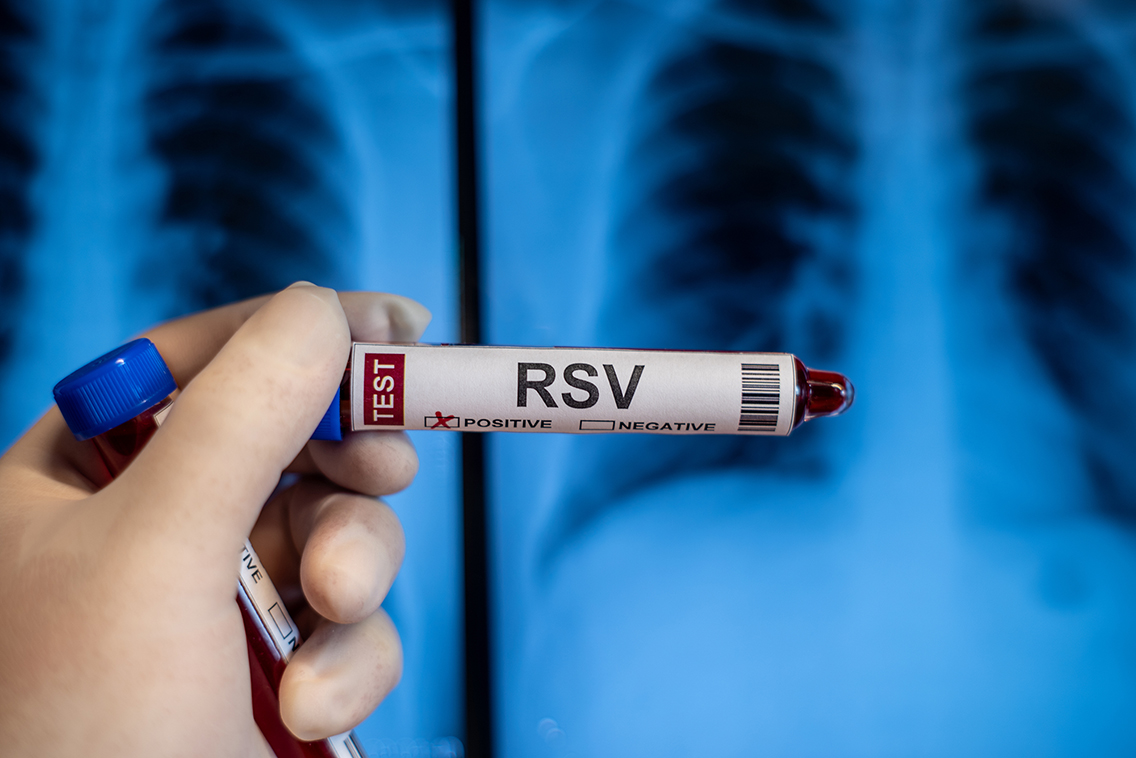

New Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine

COVID-19 has stolen the limelight from other respiratory viruses in recent years. However there are plenty of other common viruses which can have serious health consequences, among them Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV.

Medical Advances

An end in sight for AIDS

A new UN report reveals optimism about a possible end to the global AIDS epidemic

Medical Advances

Anti-vaccine sentiment increases risk of measles outbreaks

Vaccine technologies have continued to improve greatly in recent years. However, vaccines are little use if people refuse to use them. Here we look at the precarious position of measles, a well-known but little-understood serious condition, which is held in check in most countries only because of high vaccine uptake.

Medical Advances

Does a common sweetener cause cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of the WHO, recently classified the common sweetener aspartame as a possible cause of cancer in humans.

Protection

Building a sustainable protection market

Beneath the Surface report 2023 We explored some of the key drivers of sustainability for the protection market. We undertook consumer research which combined with our medical and underwriting expertise and our deep understanding of the market, enabled us to create this report.

.png)

Protection

Navigating the ocean of Value-Added Services

Beneath the Surface report 2022 In this report, we analyse the current VAS landscape in the UK & Irish protection markets. Look to understand the views and experiences of customers, with the aim of assessing how much value these services are really adding today. Look at what insurers say, and consider what the future might hold for the development of VAS.

.png)