Mike Wilson | AVP, Medical Analytics | July 2024

Article summary:

- Despite broadly improving cancer mortality, some types of the disease are increasing in incidence.

- One notable example is colorectal (bowel) cancer, which is increasing among cohorts of people aged under 50 in some countries, including the US, UK, Canada and Australia.

- Leading theories to explain this include diets high in processed meats, low in fibre, and accompanied by high alcohol consumption.

- Many other theories exist, including gut bacteria, pollution and chemicals in food. Funding is increasing in order to answer this question but at present the precise causes remain unknown.

Cancer mortality is decreasing around the world

With each passing year, scientists understand more about the mechanisms of the disease, and doctors have more and better tools available to diagnose and treat cancer in all of its forms. However, although the medical pipeline remains promisingly full, the story is not a universally positive one. In this article we look at how headline improvements in mortality can mask underlying worsening incidence trends for some cancers among specific cohorts.

US data for the years 2015 to 2019 show that almost half of the most common cancer types exhibited increasing incidence rates, including cancers of the prostate, uterus and kidney, yet overall rates were flat over this period.

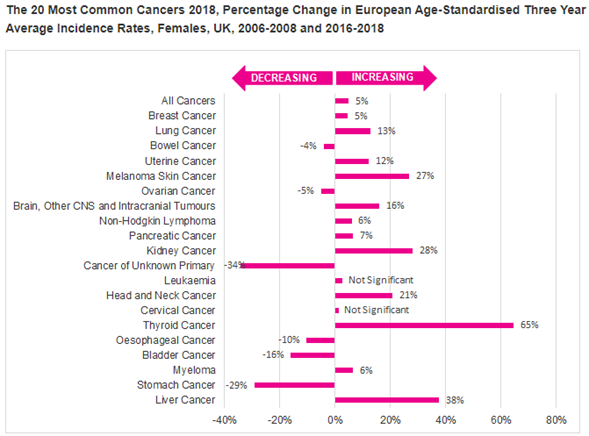

In the UK, total incidence between the early 1990s and 2018 increased by 12%, with uneven experience between the sexes. Cancers in women increased by 16%, but among men, the increase was only around 3%. The cancers with the highest overall increases in the UK include thyroid, liver, kidney and skin.[1] The data covers a slightly different timeframe but it is still remarkable that the picture differs so much between the two nations. Note the figures for the UK, below, are for a 10-year period and are cumulative, while the US figures are for a 5-year period and expressed as annual averages.

In Asian markets, trends vary but several cancers exhibit upward incidence trends, including thyroid, breast, pancreatic and colorectal cancers. Some of these may be due to screening availability and uptake, for example thyroid cancer. Rates of breast cancer incidence are growing most in low- and middle-income markets. While screening policies and behaviours play a part, this likely reflects the increased prevalence of underlying risk factors as countries experience economic development. Apart from the presence of more people at susceptible ages these can include obesity, physical inactivity and chronic exposure to contraceptive pills.[1]

Cancer incidence is a function of several variables, including genetics, behaviour, environmental exposure and healthcare systems. One concerning recent trend affecting a broader range of countries is increased incidence of bowel/colon cancers among younger people. While the overall rates are decreasing in many countries, including the US and UK, rates are increasing at younger ages. So, what is the scale of the problem and what might be driving this?

Setting out the problem

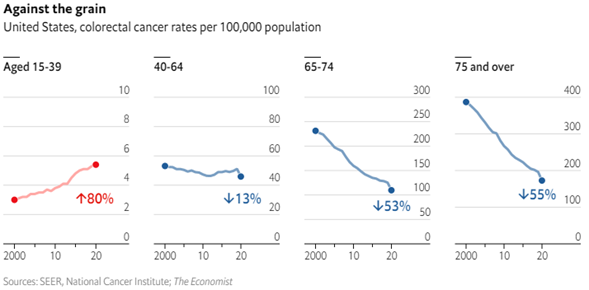

The death from colorectal cancer, aged 43, of Black Panther actor Chadwick Boseman was perhaps the most prominent instance, but cases – and deaths – among the under 50s are undoubtedly becoming more prominent. US data shows trends among younger adults bucking downward trends at older ages. Rates of colorectal cancers increased 80% among 15-39 year olds between 2000 and 2020. Note the y-axis scales – cases are much more common among older people, so the upward trend at younger ages would be drowned out by the broadly positive news among older groups if we failed to stratify by age.

In part the huge difference in incidence is because screening programmes typically only invite older people. In the US, invitations used to begin at age 50 but lowered to 45 in 2021 in response to these trends. In the UK, this age will lower from 60 to 50 in the coming years. In the absence of screening, cancers in younger people would only come to light when they become symptomatic, and are therefore more likely to be advanced when diagnosed. There are also suggestions that cancers affecting younger people are fundamentally more aggressive, for unknown reasons.

Sadly, this means these cases can often translate into mortality. UK mortality statistics show that at ages typical of protection insurance, deaths from colorectal cancers were higher among women in 2022 than in 2001, with a 10-20% reduction in rates in the first half of this period completely reversed by a decade of increases more recently. Among men, a more muted version of this pattern means recent death rates remain well below 2001 levels, but are also heading in the wrong direction.[CJ1] [CJ2] [CJ3] Similar trends have also been documented in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and some parts of Europe and Asia.[1]

Increases among young people in East Asian markets stand out less, as rates of colorectal cancer have broadly increased in the past 30 years at all ages. This appears most likely due to the ‘westernisation’ of cultures, with changing diets, more sedentary lifestyles and high levels of alcohol consumption.[2] However, trends are worse among the young. In data covering approximately 20 years up to 2007, rates of colorectal cancers increased significantly among those under 50 in Japan and parts of China, whereas among those over 50, rates were either not increasing (China) or increasing more slowly (Japan).[3]

[1] Colorectal Cancer Rising among Young Adults - NCI

[2] Updated epidemiology of gastrointestinal cancers in East Asia - PubMed (nih.gov)

What is causing this?

Recent trends have been identified as a concern by the scientific community. If there were a single, simple cause it would likely be known by now, so we expect the answer to be multifactorial. While genetics may play a part for some, this accounts for only a minority of young-onset cases, estimated at 10-20%. Instead, the emerging data suggests cohort effects, that is to say the increase may be associated with the current generation of younger adults. That the increase is associated with a particular generation tentatively suggests the key factors may be environmental or behavioural, rather than strictly biological.

Contributing causes likely include diet, with possible links to obesity and gut flora. Certainly the rise in colorectal cancers broadly coincide with increases in obesity in countries with more notable trends. More specifically, scientists suspect diets high in processed meat and fat, and low in fibrous fruit and vegetables, may play a part. Unhealthy diets are more common in recent years, and contribute to the obesity trends mentioned above.

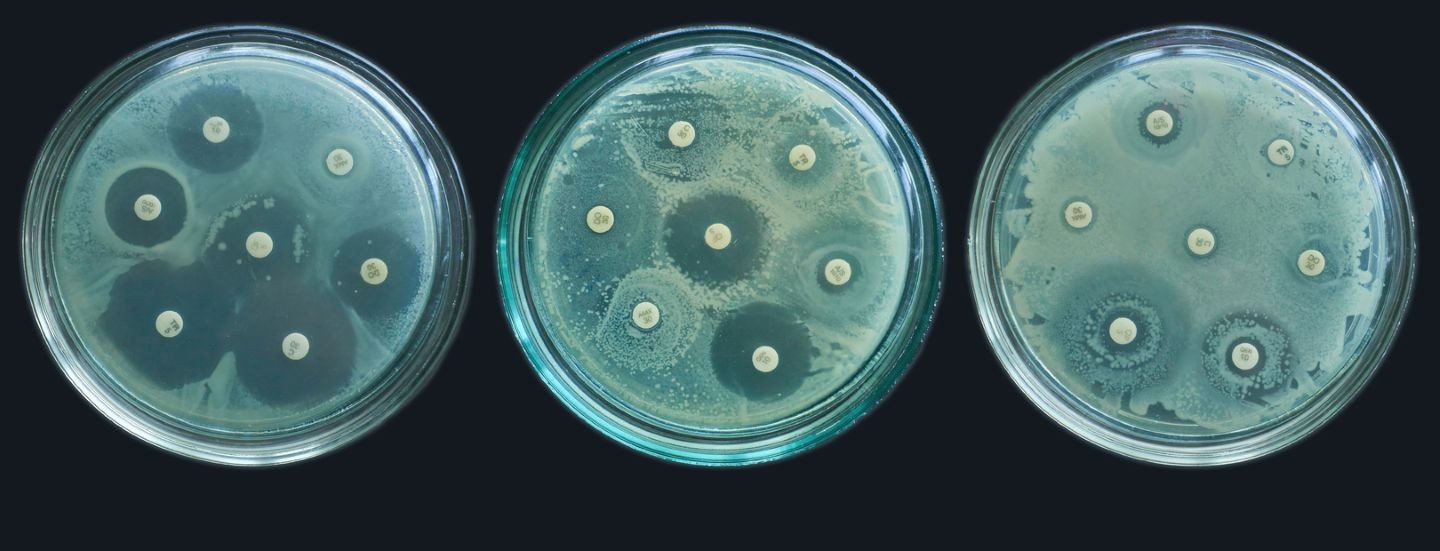

A recent Chinese study suggested a link between three types of bacteria and some aggressive forms of colorectal cancer – those with a so-called KRAS mutation. Other bacteria, including some found in probiotic yoghurts, were tentatively thought to be protective, as they were more common in people with less aggressive cancers.[1] Previous studies have associated the more worrying bacteria with diets high in processed meats, especially red meats, and refined grains like white rice, couscous and cornflakes.

Related contributory factors may include blood sugar levels and diabetes, as well as gut inflammation, which is often caused by diet, and which can cause harmful carcinogenic effects. However, we should note that a significant minority of cases occur in people with healthy weights and good diets, so obvious dietary contributors cannot tell us the whole story.

Other theories relate to increasing alcohol use. Colorectal cancer rates in the UK diverged from some European peers and this broadly correlates with steep increases in alcohol consumption among younger Britons not mirrored in, say, France or Italy.[2] Other potential culprits include air and water pollution, antibiotic use, chemicals in soil and food and pesticides infiltrating food sources. Smoking is also cited, though while it surely doesn’t help, this behaviour has generally become less common during the period in question.

For all of these causes, questions remain about how the impact is being felt so strongly among younger generations, but apparently barely at all among older people in many markets. This remains a mystery. It may be that older ages are susceptible to the factors driving this trend, but that the effects are being ‘drowned out’ by other factors associated with improvements, but it remains possible that an as yet unknown factor, or combination of factors, is behind the trends seen among younger people.

[2] Obesity and binge drinking driving up bowel cancer rates in young people in UK | The Independent

What next? Investigating the exposome

It should by now be clear that nobody really knows why young people are suffering more colorectal cancers, with theories attempting to explain the phenomenon abounding. Naturally, digging into this is important. Recently a 5-year research project received funding in order to hopefully provide answers. It will use stored samples of blood, urine and faeces from biobanks across Europe, North America and India, and aims to broadly consider all sorts of things people are exposed to, including food, drink, medicines, pollutants and other chemicals. This represents an attempt to comprehensively study the role played by the human ‘exposome’. The exposome is the sum total of all the things an individual is exposed to, from before birth up to present day, specifically relating to health.

Stool samples in particular could be important as they will allow scientists to analyse gut bacteria. One participating biobank contains a dried spot of blood from almost every baby born in Denmark since 1982, which could help reveal the role played by exposures in the womb.[1]

This study, and others, will urgently seek answers in the hope that people may be able make modifications to their behaviour in order to reduce their risks of developing this disease, especially at such young ages.

[1] The hunt is on to learn why bowel cancer in young people is rising | New Scientist

Insurance implications

Increasing cases of colorectal cancer would tend to negatively impact a broad range of protection products. Taken in isolation, this trend means more cases of colorectal cancer which in turn means more mortality at protection ages. There would be no material longevity offset as the affected ages are so young. Critical illness products would also typically respond to these diagnoses with full claim payments.

However, we should remember that the broader context is of decreasing incidence and mortality among older adults and at present the latter is more significant as – even at protection ages – more customers are at ages where rates are decreasing. Nonetheless, the early nature, and slow progression, of this likely cohort effect leaves open the possibility that these increases may impact progressively older lives as the affected cohort ages. This means the relatively small numbers of people impacted could grow larger as the at-risk cohort reaches ages where normal causes of colorectal cancer are more common. We should bear this in mind when deriving future trends for cancer incidence and mortality in markets where this phenomenon manifests.

Without knowing the cause it is difficult to comment on the possible socioeconomic profile of those who are driving this trend. Should factors such as poor diet and alcohol excess predominate then we could expect to see a disproportionate number of cases occurring outside the insured population.

Mike Wilson

AVP | Medical Analytics

.png)

.png)

.png)