This website uses cookies for a variety of purposes including to help improve our website, and for other reasons as set out in our privacy policy. By using our website, you acknowledge and consent to the use of essential and analytics cookies, as described in our Cookie Policy. To understand more about how we use cookies or to change your preference and browser settings, please see our Cookie Policy.

Medical Analytics | 10 August 2023

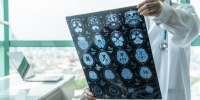

The world’s largest conference dedicated to the science and treatment of cancer took place in Chicago in early June. The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting is a popular forum at which new scientific developments are often revealed. This year was no different and it included the presentation of over 250 abstracts of new research and around 2,000 others presented in brief written form. Here we focus on new diagnostic techniques aiming to diagnose cancer at earlier stages.

Early detection of cancer

Cancer is easier to treat if it is diagnosed early. Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests are being developed which aim to detect cancers at more treatable stages. These tests seek to identify fragments of DNA circulating in blood which have been released by cancers. The ability to diagnose (or rule out) cancer using a simple, minimally invasive test could be extremely valuable. Data from a recent trial sheds light on how effective the technology currently is and what its major limitations are.

Trial update

The SYMPLIFY trial enrolled over 6,000 patients in England and Wales who were already suspected of having cancer. They were referred to a hospital and investigated in the normal way, but in addition to typical investigations also had a blood test known as Galleri, developed by US company Grail.

Galleri is a leading MCED test based on earlier trials.

The following high-level findings were presented in Chicago and have since been published in a peer reviewed paper. When the test said a person had cancer, they truly did have cancer 76% of the time. When it said they did not have cancer, this was true 98% of the time. Overall accuracy was 66%.

However, accuracy varied a great deal depending on how advanced the cancer was and where it was in the body. While accuracy was 95% for late-stage cancers, it fell to below 25% for cancers at their earliest stages. These results are consistent with earlier trials of this technology and highlight a key limitation of MCED tests in their current form.

These tests would have greatest utility if they could detect cancers at earlier stages than otherwise detectable with current technology. Successfully detecting a late-stage cancer therefore offers, only minimal benefits, because treatment options and survival probabilities are more limited for these patients no matter how their cancer is found. More significant benefits would occur if a patient with vague symptoms (or no symptoms) could have cancer detected at early stages before it has progressed so far. Clearly these results suggest success identifying early-stage cancers presents a larger challenge – one the technology currently often fails to meet.

However, the data so far does suggest a real possibility of significantly improving early-stage diagnosis rates of many cancers for which there is currently no screening programme.

If the test proved sufficiently effective it might find a role as a screening tool, possibly alongside existing screening methods, or as a common blood test when patients present with vague symptoms, like pain or fatigue, which might be due to cancer but whose cause is usually more benign. It’s worth pointing out that the headline accuracy figures reported above would lower significantly if the test was to be adopted in these roles.

We have seen the test is better at finding more advanced cancers, and the accuracy levels above are a product of the SYMPLIFY trial focusing on people already strongly suspected of having cancer, for example because they presented with a worrying symptom. This trial design allowed people with cancer to come to light relatively quickly, which accelerates the trial.

However, this is not a point in the patient’s care pathway where clinicians expect MCEDs to be at their most effective. If used as a screening tool in the general population, the great majority of patients would have no cancer, and those who did have cancer would tend on average towards having earlier-stage disease, which this MCED is less good at detecting. This doesn’t preclude its use, but needs to be considered by policymakers.

Other trials needed

What we need then, is a trial to look at how useful it might be in a more realistic scenario. Luckily another trial is ongoing which should do just that. The NHS-Galleri trial has enrolled 140,000 patients in England and Wales between the ages of 50 and 77.

The participants will attend three appointments over two years, each of which includes a blood test, but only half will be tested with Galleri’s test. Other than their age, there is no specific reason to suspect cancer in these people. In fact, they must not have had cancer recently in order to sign up to the trial. This large trial therefore needs more time to allow cancers to naturally emerge in the enrolled group, but when they do it should provide insight into how many cancer diagnoses can be accelerated by this technology and – once more time passes – whether it can materially improve patient outcomes.

Early (interim) results from this trial could be available by the end of this year.

In the UK, any decision on whether to adopt the technology, and in which situations, would occur only after this larger trial concludes. In other markets, adoption of the technology could be very different in terms of when and in which situations it is used, with variables including cost, funding and patient demand.

Data from a similar study in the US suggests the technology has significant limitations. The test produced relatively few false positives – around 1 in every 200 people without cancer were told they might have it. However, it was only able to pick up around one in five cases of cancer.

Breath tests

In a separate development, scientists in the UK have reached late-stage trials of technology aimed at diagnosing cancer via breath samples. Primarily aimed at finding cancers of the alimentary canal (oesophagus, stomach, colon) plus the pancreas and liver, these tests take advantage of the fact some compounds change in concentration in the gut when cancer is present and can be detected in breath samples. If effective, this sort of technology could be relatively inexpensive and non-invasive, but we must first await a trial involving 20,000 patients taking place over the next three years to determine if it is sufficiently accurate to play a significant role in diagnosing cancers early.

Conclusion

What does this mean for cancer patients and insurers?

Should this technology prove successful, it would be enormously beneficial to society, improving quality and length of life for many.

For insurers, the impact could be mixed. Those writing mortality products would tend to benefit from higher proportions of cancers being diagnosed at early stages when treatments are more effective. This would reduce, or defer, payments relating to death from cancer.

Insurers writing other products could face challenges. Chief among these would relate to products paying claims on diagnoses of cancer.

It is reasonable to assume these technologies would cause some claims to manifest many months, even years, earlier than they otherwise would. This impacts the premiums collected and interest earned on affected policies. Some cancers which might have occurred beyond the end of fixed terms could now be within the period of coverage, and decreasing covers would typically pay higher amounts. Scope for using this technology to detect disease at pre-cancerous stages appears limited. We therefore cannot expect a material offset whereby some cancers are prevented altogether by this technology.

Insurers writing cancer-specific products would face more concentrated risk, while products covering a wider range of critical illnesses would experience more diluted impacts. Increased life expectancies would bring challenges for longevity business with any offsets against mortality protection being sensitive to the age mix of the respective portfolios.

Actual impacts will depend on how the tests are used. Broad adoption as part of national screening programmes or low-cost, widespread incorporation into private healthcare plans would tend to lead to more significant effects.

The engagement of the insured population with this technology remains a key unknown.

References

- SYMPLIFY — Oxford Cancer

- Multi-cancer early detection test in symptomatic patients referred for cancer investigation in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY): a large-scale, observational cohort study - The Lancet Oncology

- ASCO: Grail’s cancer blood test ‘promising’ in UK trial | pharmaphorum

- Even in this high-risk group, most people did not have cancer, so the 2% inaccuracy among all people told they did not have cancer accounts for quite a large number of people. On only around two-thirds of occasions where the tests said a person had cancer was it correct to do so. False positives can cause significant patient anxiety, though note existing screening techniques also have false positives, and these represent the fairest comparison.

- NHS-Galleri Trial | Detecting cancer early

- The other half of samples will be stored. They may be tested in future, but they form the control group and so no test will be performed as part of the initial trial.

- Esmo 2022 – Galleri’s real-world exhibition disappoints | Evaluate

- UK trials for cancer breath tests reach final stages | Cancer | The Guardian

Pacific Life Re Limited (No. 825110) is registered in England and Wales and has its registered office at Tower Bridge House, St Katharine’s Way, London, E1W 1BA. Pacific Life Re Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulatory Authority in the United Kingdom (Reference Number 202620). The material contained in this booklet is for information purposes only. Pacific Life Re gives no assurance as to the completeness or accuracy of such material and accepts no responsibility for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting on the basis of such material.

©2023 Pacific Life Re Limited. All rights reserved.

Ian Collins

Vice President

Mike Wilson

Associate Vice President

Discover more Vital Insights

Protection

Changing regulations an area of opportunity for reinsurers

When asked what opportunities life reinsurers in Asia have, Pacific Life Re's Vasan Errakiah was quick to cite demand for insurance, changing regulations and the adoption of new technologies.

.png)

Protection

Solving the implementation puzzle of machine learning

Asia Insurance Review spoke to Pacific Life Re's Mr Ong Qian Hao and FWD Group's Ms Fiona Hermans to understand how strategic partnerships can effectively address these challenges and lead to successful outcomes.

Medical Advances

Update on COVID-19 and Long Covid

Read our update on the impact of mortality from COVID-19.

Medical Advances

Lung cancer screening, marginal gains or a game changer?

Lung cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage leading to poor prognosis for the individual. We look at how screening could have an impact.

Underwriting & Claims

From Barrier to Benefit: Rethinking the Future of Underwriting

Underwriting has been going through significant transformation over the last few years and continues to accelerate at an unprecedented pace. Traditionally seen as a barrier, there is now a growing opportunity to position underwriting as a strategic asset.

Protection

Leveraging big data insights in reinsurance

Big data analytics has been instrumental for (re)insurers aiming to boost performance, efficiency, and effectiveness.

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 2

From emerging drugs which battle obesity to a review of the effectiveness of new blood tests both to detect cancer and to help slow down Alzheimer’s, we hope these insights help keep you up to date with the latest in medical research.

Medical Advances

Vaping vs. smoking: what are the risks?

Vaping is generally considered less harmful than smoking, however longer-term risks have not had time to emerge and could prove considerable.

Medical Advances

Gut Check: the concerning rise of bowel cancer among young adults

Despite broadly improving cancer mortality, some types of the disease are increasing in incidence

Protection

Serving the Underserved

Consumer Duty has put increased focus on how much value different customers get from financial products. But how well is the protection industry serving different customer groups? Who are the most underserved groups, and what can the industry do to help serve these groups better?

Underwriting & Claims

The future of underwriting is now... are we ready?

Underwriting processes, practices and philosophies are changing with faster pace than we have ever experienced before.

Medical Advances

Tackling the obesity crisis

A new generation of drugs has now well and truly arrived aiming to improve weight loss. The drugs are heavily touted by celebrities and influencers, despite many of them having no medical need to lose weight. Obesity contributes significantly to some of the most common causes of death including heart disease and cancer, as well as affecting quality of life for millions. In this article we look at these increasingly available drugs offering hope to more people with obesity. We consider their potential to broadly improve health, and their limitations.

Medical Advances

New drug may slow down multiple sclerosis

Scientists successfully conducted early-stage trials which provide hope of a future cure for some of the most severe types of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Medical Advances

Exploring the latest medical advances in cancer detection

The world’s largest conference dedicated to the science and treatment of cancer took place in Chicago in early June. The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting is a popular forum at which new scientific developments are often revealed.

Medical Advances

Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumour (PitNET)

A recent review by WHO resulted in reclassification of pituitary adenoma as described in the article

Medical Advances

Climate change and its impact on mortality and morbidity

In 2023 we’ve seen soaring temperatures across the globe along with devastating storms and wildfires. Why is our climate changing and what impact is it having?

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 1

Welcome to our first edition of Vital Insights. Here we’ve put together a collection of articles covering some of the major issues of the day with a specific focus on how they will impact mortality and morbidity.

Medical Advances

Deep dive: Alzheimer's

Total deaths from dementias in high-income countries have almost quadrupled in the last 20 years, yet so far medical science has very few answers. This article looks at the recent emergence of the first drugs which may be able to modify the effects of this terrifying disease

Medical Advances

New Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine

COVID-19 has stolen the limelight from other respiratory viruses in recent years. However there are plenty of other common viruses which can have serious health consequences, among them Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV.

Medical Advances

An end in sight for AIDS

A new UN report reveals optimism about a possible end to the global AIDS epidemic

Medical Advances

Anti-vaccine sentiment increases risk of measles outbreaks

Vaccine technologies have continued to improve greatly in recent years. However, vaccines are little use if people refuse to use them. Here we look at the precarious position of measles, a well-known but little-understood serious condition, which is held in check in most countries only because of high vaccine uptake.

Medical Advances

Does a common sweetener cause cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of the WHO, recently classified the common sweetener aspartame as a possible cause of cancer in humans.

Protection

Building a sustainable protection market

Beneath the Surface report 2023 We explored some of the key drivers of sustainability for the protection market. We undertook consumer research which combined with our medical and underwriting expertise and our deep understanding of the market, enabled us to create this report.

.png)

Protection

Navigating the ocean of Value-Added Services

Beneath the Surface report 2022 In this report, we analyse the current VAS landscape in the UK & Irish protection markets. Look to understand the views and experiences of customers, with the aim of assessing how much value these services are really adding today. Look at what insurers say, and consider what the future might hold for the development of VAS.

.png)