This website uses cookies for a variety of purposes including to help improve our website, and for other reasons as set out in our privacy policy. By using our website, you acknowledge and consent to the use of essential and analytics cookies, as described in our Cookie Policy. To understand more about how we use cookies or to change your preference and browser settings, please see our Cookie Policy.

See Lek Chew | 20 December 2023

Is it just me, or is the weather crazy this year?

Summer 2023 in the northern hemisphere was the hottest in human history1. In fact, as illustrated below, this was by some distance. The June-August season was 0.66°C (1.19°F) above average summers and around 0.30°C (0.54°F) hotter than any prior season.

However, talk of fractions of a degree are quite easy to write off as inconsequential. Risks to life, health and property derive not from slight increases in average temperature, but from extreme events downstream of these. While extreme events have always occurred, the number and intensity of these have without doubt increased. 2023 has seen more than its fair share of climate-related disasters.

In North America, periods of hot and dry weather led to significant wildfires, including the destruction in August of the Hawaiian town of Lahaina in the state’s worst natural disaster, and the deadliest fire in modern US history2. In California, scientists believe climate change was a significant factor contributing to the huge increase in land area affected by wildfires during summer months. Many other parts of the United States and (especially) Canada were also affected by fires this summer. In Canada, the area burned3 was over 170,000km3, which is around half the size of Germany.

Record-breaking heatwaves in Southern Europe and Turkey saw temperatures over 45°C for extended periods, including in Greece and Italy where extensive fires, especially on Sicily, caused significant damage4. In South America, despite July being mid-winter, some parts of Argentina and Chile set extraordinary all-time temperature records, more than 20°C above normal for the time of year5.

Severe droughts also occurred in many parts of the world, including several parts of Europe6 with the resulting negative impact on crop yields and water supply.

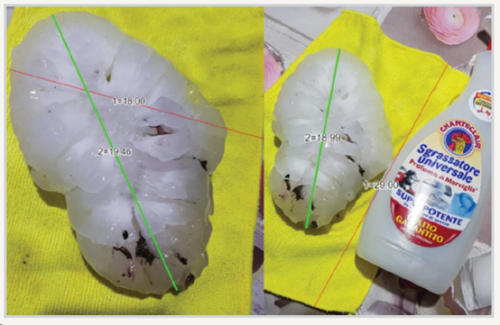

To make things worse, on top of sweltering temperatures, several regions including Beijing in China7, Fukuoka and Oita in Japan8 and parts of South Korea9 also experienced torrential rainfall, with flooding and landslides. Australia has also seen flooding in recent seasons, including in New South Wales in late 2022 which became the nation’s most expensive natural disaster10. More recently, thousands died in flooding in Libya in September. There were heatwaves in southern Italy as well as extreme hailstorms in the north of the country which produced the largest hailstone ever found in Europe. As can be seen below, it was 19cm long.

What is causing all of this?

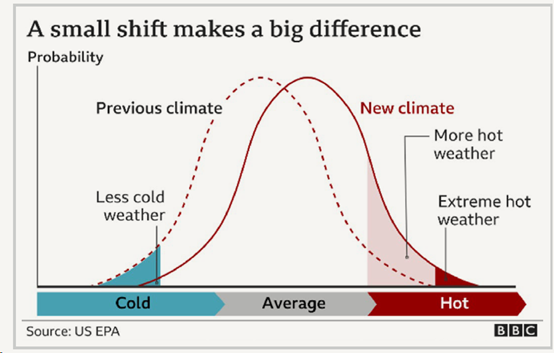

These events are not coincidental. Recently, global sea surface temperatures have escalated at an unparalleled pace to hit record highs11. This is thought to be due to a combination of drivers, including long-term human-induced global warming and the so-called El Niño phenomenon. El Niño is a recurring event which is part of cyclical variations in winds and sea temperatures. It affects ocean currents causing the release of extra heat from warmer waters into the atmosphere to drive air temperatures up, with wide ranging consequences, including more extreme weather conditions. A slight rise in average temperatures has a significant impact because it causes the entire range of daily temperatures to shift towards warmer levels, increasing the likelihood and intensity of days with more extreme heat.

This is shown below, but note that it may be more likely the distribution of typical daily temperatures widens, rather than uniformly shifting toward the right (i.e. towards hot days). One consequence of this would be that we might see more hot days without necessarily seeing so many fewer cold days as we might expect, with implications for mortality assessed below.

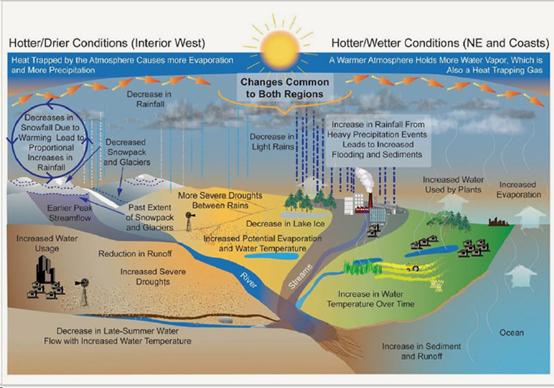

Water vapour has played a vital role in sustaining a habitable temperature on earth for eons. In fact, without it, the planet’s surface temperature would plummet to around 33°C (59°F) colder than it is now! Warm air holds about 7% more water vapour, per 1°C increase in temperature12. Hence warmer air richer in water vapour prevents more heat from escaping, absorbing it instead creating a so-called ‘positive feedback loop’13.

However, at higher temperatures, increased concentrations of water vapour in the air exacerbate the greenhouse effect. In fact, water vapour is the most abundant greenhouse gas on earth, responsible for approximately 50% of the greenhouse effect, through which the sun’s heat is trapped in earth’s atmosphere. It is likely this process was further exacerbated by a large sub-sea volcanic eruption in Tonga in 2021 which released an unusual quantity of water vapour into the atmosphere.

Water vapour is also a critical component of the planet’s water cycle, facilitating the movement of water in various forms throughout the atmosphere, land, and oceans. Warmer temperatures speed up the water cycle which aggravates weather conditions. Wet regions become wetter and dry regions become drier, the mechanisms for which are shown in the graphic below14. As air contains more water vapour, it also holds more latent heat that fuels intense windstorms and thunderstorms.

The acceleration of evaporation of water from land also results in soil drying out. Instead of infiltrating the soil, subsequent intense rainfall on parched ground increases the rate of water runoff into rivers and streams, increasing flood risk.

There is one additional factor which may contribute to the sudden increase in sea and air temperatures, which can best be described as ironic. Global shipping is a material contributor to air pollution. Measures to reduce sulphur emissions from ships include strict new measures mandating use of low-sulphur fuels. However, it turns out sulphur emissions in the atmosphere were helping to reflect some heat away from the planet. Since the change has been successful, there is now a lot less sulphur in the air, with the undesirable side-effect that more heat from the sun now reaches the surface of the planet. In effect, this pollution was masking some of the effects of climate change, especially in the busy shipping lanes shown on the following page. The sudden change is the equivalent to around two additional years of emissions and its effect is concentrated on the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans15.

What does this mean for Life and Health insurers?

Mortality and morbidity impacts

Despite the increased number of climate-related natural disasters, their impact on overall mortality is currently minimal, especially in high-income countries. Therefore, even the noted increase in such events may have a muted impact on future mortality. Naturally the impacts will vary by territory depending on factors including local climate, health infrastructure and underlying health of the population.

Despite growing prominence of wildfires, and the recent sad death toll in Hawaii of 97, the direct impact of fires on population mortality rates is typically modest. The resulting pollutants can also have secondary impacts on morbidity, for example by worsening respiratory conditions. However, these are harder to calculate. One study estimated that across a large area of central California with a total population in excess of 10 million, exposure to unhealthy particles known as PM2·5 during the California wildfires of October 2017 resulted in an additional 308 respiratory, cardiovascular, and asthma-related hospital admissions16.

Heatwaves

Heatwaves are probably the most consequential events for human health as they can affect large, populated areas for extended periods. Still, we should recall that in temperate climates there are typically more deaths associated with cold weather than hot weather, and that if periods of intense cold reduce as part of climate change there may be substantial offsets to any increase in summer deaths. Hence, on balance, they are unlikely to be a strong driver of additional impacts on population health or, consequently, on life and health insurance books in such markets over the medium term. However, some reasonable future predictions suggest this impact may not initially happen as neatly as this logic suggests. Instead of all temperatures shifting uniformly upwards as the climate warms, the range of daily temperatures may widen. This would mean more hot days, but initially little reduction in cold ones, reducing any mortality offset we might otherwise expect due to a reduction in the number and intensity of periods of cold. The annual pattern of deaths, currently materially more concentrated in winter months, may slowly change. The medium-term prospects are less clear, with uncertainty around the trajectory of average temperatures as well as our collective ability to make necessary changes to global infrastructure including in relation to power generation, transportation, agriculture and water management.

Heatwaves damage health by causing illnesses like heatstroke. In hot weather, blood vessels dilate so that more blood can flow towards our skin and cool us down. However, dilating blood vessels force our heart to work harder. This means that those at highest risk in hot weather are those with existing cardiovascular problems. We might also see respiratory conditions increase in number and severity. Poorer air quality is likely to accompany climate change and higher concentrations of pollutants can exacerbate conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Infectious diseases

Incremental changes in the dynamics affecting circulation of infectious diseases are also likely. This includes vector-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria. For example, a recent paper (not yet peer-reviewed) found that climate change has driven expansion of dengue fever risk in Vietnam (17). Some cases of locally-acquired dengue fever were also identified in Italy and France this year. This is highly atypical (18). While these diseases are mainly influenced by increasingly warm temperatures, others also relate to weather becoming increasingly wet, including West Nile virus.

All of the above impacts are likely to be slow and, in higher-income locations, relatively small overall. In all cases, vulnerable groups, such as children and the elderly, are expected to be more adversely affected due to their heightened susceptibility to the health impacts of climate change.

Economic impacts

Long-term sustainability is increasingly recognised as an important feature of investment assets. Some of this is altruistic, but there are also significant risks associated with entities materially exposed to less sustainable practices such as heavy usage of carbon. These entities may face higher costs of doing business and associated significant shifts in asset values.

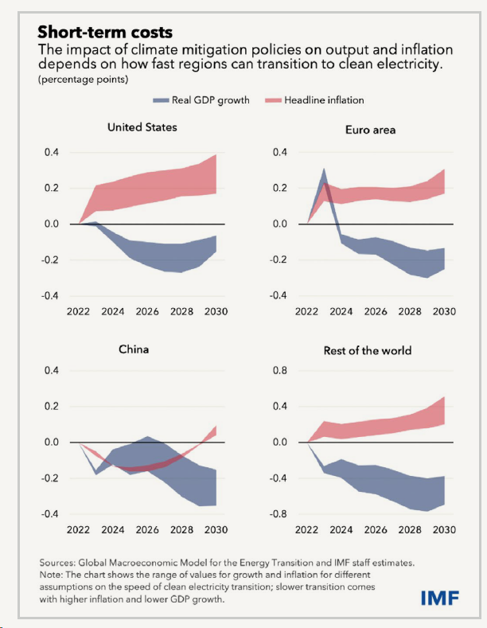

Achieving progress towards sustainability will undoubtedly entail short- to medium-term economic costs concentrated in, but by no means limited to, the companies most exposed to these transition risks. The chart on the following page shows the IMF’s anticipated range of impacts on entire economies of the transition to clean energy on GDP (blue) and inflation (red).

In addition to encouraging the above changes, the impacts of climate change can also exacerbate economic pressures.

For example, increased costs of food due to climate related periods of scarcity would encourage inflationary pressures. The indirect impacts of periods of recession or austerity on health and healthcare may yet prove to be more material in terms of mortality and morbidity outcomes in the long term than the physical risks discussed above.

Conclusion

Climate change already affects many aspects of our lives. Seemingly small rises in temperature can, and already do, cause a proliferation of headline-grabbing natural disasters on every continent, with direct implications for human health. As devastating as these events are, some of the largest impacts for life and health insurers likely lie elsewhere. The gradual increase in number and intensity of heatwaves; changing patterns of pollution, and of infectious diseases; and longer-term knock-on impacts from economic disruption all represent more insidious, but potentially materially more impactful, ways in which the issue can impact the health of insurers, and the lives they insure.

References

- Summer 2023: the hottest on record | Copernicus; Note ‘boreal’ in the accompanying chart refers broadly to the northern hemisphere

- Lahaina blaze now the deadliest in modern U.S. history: Recap (nbcnews.com)

- California wildfires are five times bigger now due to climate change: Study (straitstimes.com)

- ‘This is just the beginning’: Extreme heat around the world as fires rage in southern Europe (cnn.com)

- South America is topping 100 degrees, even though it’s winter - The Washington Post

- Variable drought conditions keep affecting large parts of Europe, new report shows (europa.eu)

- China: 31,000 forced to flee homes in Beijing as Typhoon Doksuri brings heavy rains (theguardian.com)

- One dead as Japan warns of ‘heaviest rain ever’ in southwest (channelnewsasia.com)

- South Korea floods: Dozens die in flooded tunnel and landslides (bbc.com)

- Australian floods and triple La Niña | Royal Meteorological Society (rmets.org)

- Ocean heat is off the charts (theconversation.com)

- AR6 Report: Chapter 8 - Water Cycle Changes (ipcc.ch)

- Steamy Relationships: How Atmospheric Water Vapor Amplifies Earth’s Greenhouse Effect – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet (nasa.gov)

- Climate Impacts on Water Resources | Climate Change Impacts | US EPA

- Climate Impact of Decreasing Atmospheric Sulphate Aerosols and the Risk of a Termination Shock (columbia.edu)

- Estimating the Acute Health Impacts of Fire-Originated PM2.5 Exposure During the 2017 California Wildfires (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- Interactions between climate change, urban infrastructure and mobility are driving dengue emergence in Vietnam (medrxiv.org)

- Dengue worldwide overview (europa.eu)

Pacific Life Re Limited (No. 825110) is registered in England and Wales and has its registered office at Tower Bridge House, St Katharine’s Way, London, E1W 1BA. Pacific Life Re Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulatory Authority in the United Kingdom (Reference Number 202620). The material contained in this booklet is for information purposes only. Pacific Life Re gives no assurance as to the completeness or accuracy of such material and accepts no responsibility for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting on the basis of such material.

©2024 Pacific Life Re Limited. All rights reserved.

See Lek Chew

R&D Actuary

Discover more Vital Insights

Protection

Changing regulations an area of opportunity for reinsurers

When asked what opportunities life reinsurers in Asia have, Pacific Life Re's Vasan Errakiah was quick to cite demand for insurance, changing regulations and the adoption of new technologies.

.png)

Protection

Solving the implementation puzzle of machine learning

Asia Insurance Review spoke to Pacific Life Re's Mr Ong Qian Hao and FWD Group's Ms Fiona Hermans to understand how strategic partnerships can effectively address these challenges and lead to successful outcomes.

Medical Advances

Update on COVID-19 and Long Covid

Read our update on the impact of mortality from COVID-19.

Medical Advances

Lung cancer screening, marginal gains or a game changer?

Lung cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage leading to poor prognosis for the individual. We look at how screening could have an impact.

Underwriting & Claims

From Barrier to Benefit: Rethinking the Future of Underwriting

Underwriting has been going through significant transformation over the last few years and continues to accelerate at an unprecedented pace. Traditionally seen as a barrier, there is now a growing opportunity to position underwriting as a strategic asset.

Protection

Leveraging big data insights in reinsurance

Big data analytics has been instrumental for (re)insurers aiming to boost performance, efficiency, and effectiveness.

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 2

From emerging drugs which battle obesity to a review of the effectiveness of new blood tests both to detect cancer and to help slow down Alzheimer’s, we hope these insights help keep you up to date with the latest in medical research.

Medical Advances

Vaping vs. smoking: what are the risks?

Vaping is generally considered less harmful than smoking, however longer-term risks have not had time to emerge and could prove considerable.

Medical Advances

Gut Check: the concerning rise of bowel cancer among young adults

Despite broadly improving cancer mortality, some types of the disease are increasing in incidence

Protection

Serving the Underserved

Consumer Duty has put increased focus on how much value different customers get from financial products. But how well is the protection industry serving different customer groups? Who are the most underserved groups, and what can the industry do to help serve these groups better?

Underwriting & Claims

The future of underwriting is now... are we ready?

Underwriting processes, practices and philosophies are changing with faster pace than we have ever experienced before.

Medical Advances

Tackling the obesity crisis

A new generation of drugs has now well and truly arrived aiming to improve weight loss. The drugs are heavily touted by celebrities and influencers, despite many of them having no medical need to lose weight. Obesity contributes significantly to some of the most common causes of death including heart disease and cancer, as well as affecting quality of life for millions. In this article we look at these increasingly available drugs offering hope to more people with obesity. We consider their potential to broadly improve health, and their limitations.

Medical Advances

New drug may slow down multiple sclerosis

Scientists successfully conducted early-stage trials which provide hope of a future cure for some of the most severe types of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Medical Advances

Exploring the latest medical advances in cancer detection

The world’s largest conference dedicated to the science and treatment of cancer took place in Chicago in early June. The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting is a popular forum at which new scientific developments are often revealed.

Medical Advances

Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumour (PitNET)

A recent review by WHO resulted in reclassification of pituitary adenoma as described in the article

Medical Advances

Climate change and its impact on mortality and morbidity

In 2023 we’ve seen soaring temperatures across the globe along with devastating storms and wildfires. Why is our climate changing and what impact is it having?

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 1

Welcome to our first edition of Vital Insights. Here we’ve put together a collection of articles covering some of the major issues of the day with a specific focus on how they will impact mortality and morbidity.

Medical Advances

Deep dive: Alzheimer's

Total deaths from dementias in high-income countries have almost quadrupled in the last 20 years, yet so far medical science has very few answers. This article looks at the recent emergence of the first drugs which may be able to modify the effects of this terrifying disease

Medical Advances

New Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine

COVID-19 has stolen the limelight from other respiratory viruses in recent years. However there are plenty of other common viruses which can have serious health consequences, among them Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV.

Medical Advances

An end in sight for AIDS

A new UN report reveals optimism about a possible end to the global AIDS epidemic

Medical Advances

Anti-vaccine sentiment increases risk of measles outbreaks

Vaccine technologies have continued to improve greatly in recent years. However, vaccines are little use if people refuse to use them. Here we look at the precarious position of measles, a well-known but little-understood serious condition, which is held in check in most countries only because of high vaccine uptake.

Medical Advances

Does a common sweetener cause cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of the WHO, recently classified the common sweetener aspartame as a possible cause of cancer in humans.

Protection

Building a sustainable protection market

Beneath the Surface report 2023 We explored some of the key drivers of sustainability for the protection market. We undertook consumer research which combined with our medical and underwriting expertise and our deep understanding of the market, enabled us to create this report.

.png)

Protection

Navigating the ocean of Value-Added Services

Beneath the Surface report 2022 In this report, we analyse the current VAS landscape in the UK & Irish protection markets. Look to understand the views and experiences of customers, with the aim of assessing how much value these services are really adding today. Look at what insurers say, and consider what the future might hold for the development of VAS.

.png)