This website uses cookies for a variety of purposes including to help improve our website, and for other reasons as set out in our privacy policy. By using our website, you acknowledge and consent to the use of essential and analytics cookies, as described in our Cookie Policy. To understand more about how we use cookies or to change your preference and browser settings, please see our Cookie Policy.

Medical Analytics | 02 February 2024

A new generation of drugs has now well and truly arrived aiming to improve weight loss. The drugs are heavily touted by celebrities and influencers, despite many of them having no medical need to lose weight. Obesity contributes significantly to some of the most common causes of death including heart disease and cancer, as well as affecting quality of life for millions.

In this article we look at these increasingly available drugs offering hope to more people with obesity. We consider their potential to broadly improve health, and their limitations.

The Obesity Issue

Being overweight kills at least 2.8 million people globally each year. In most countries it is a growing problem; the number of people with obesity has approximately trebled since 1975.1 This epidemic has provided significant headwinds for mortality improvements. Advances in medical science have driven increases in human life expectancy for decades. However, the pace of improvement noticeably slowed in the last decade, even before the pandemic. The graphic2 below shows that in many countries, cumulative improvements between 2011-16 were lower than in 2000-11.3

One key factor driving this trend is a slowdown in improvements relating to cardiovascular conditions. In part this occurred due to lesser contributions from things like improved surgical techniques and reduced smoking. However, experts believe poor diet, increasing rates of obesity and related increases in diagnoses of type 2 diabetes contribute materially to the impact seen.

A medical problem in need of a medical solution

Obesity is a complex issue and often unfairly stigmatised. For many reasons diet and exercise are insufficient remedies for a large number of affected people. Instead, factors like genetics, gut hormones and addictive behaviour either mean that diets don’t work or that people are unable to adhere to them. Other factors, including poverty, availability of healthy food, and government policy, contribute to an environment which does little to help people live optimal lifestyles.

Successfully thinking about obesity as a medical problem, rather than an individual failing, is only half the battle.

Until recently, medical options were extremely limited. For the most obese, surgery such as a gastric bypass could help, but it’s an extreme option typically thought of as a last resort. Other than that, only one drug – orlistat – was fairly commonly used, and even then, it was often unsuccessful. For everyone else the message was just diet, exercise and willpower.

Introducing GLP-1 agonists

New drugs can help to change this. A class of drugs exists which has been used in recent years to improve blood sugar control in type 2 diabetics. These have now been approved to encourage weight loss in people who do not have diabetes. There are at least seven drugs which have this action but among the most famous are liraglutide, semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Of these semaglutide is the most well-known and widely available, especially under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, of which Wegovy is the product approved specifically for weight loss. Semaglutide is generally the most widely used, partly because trials show it is effective, and partly because it requires ‘only’ a weekly injection, whereas liraglutide requires daily self-administered injections.

Tirzepatide is not yet so widely available but does appear more effective than semaglutide in trials5 and may overtake it in popularity in the medium-term.

This family of drugs is known as GLP-1 agonists. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a hormone the body produces naturally after we eat. In diabetics, these drugs help control the amounts of insulin and glucose in the body by mimicking GLP-1. When used to treat weight loss their key action is to slow the movement of food from the stomach to the intestines. People feel fuller more quickly and for longer, and eat less. GLP-1 agonists may additionally help lower the risk of heart and kidney disease, and improve blood pressure and cholesterol, but scientists are not sure yet whether that is just a secondary effect caused by weight loss, or whether the drugs directly cause these impacts.6

Focusing on semaglutide, its potential impacts are undeniable. The STEP 1 trial published in 2021 showed that over half of people taking the drug lost over 15% of their body weight inside one year, and one in three lost over 20%7. Those taking a placebo lost only around 2%.

A typical person measuring 173cm (5ft 8in) and 120kg (265lbs or 18st 13lbs) could expect their weight to fall to 102kg, which would mean a significant drop in BMI8 from 40 to 34.

This sort of drop – if sustained – could have significant impacts on mortality and morbidity. The link between weight and mortality is well-established.

For example a recent paper studying the US population found all-cause mortality, after a median follow-up of nine years, was approximately 20% higher for people with BMI 35-40 than for those with BMI 30-35, and the incremental impact on mortality is even larger at higher weights.9

This paper found that for otherwise healthy people who had never smoked, relative to people with an ideal weight of BMI 22.5- 24.9:

- People with BMI 30.0-34.9 had mortality 21% higher

- People with BMI 35.0-39.9 had mortality 44% higher

- People with BMI over 40 had mortality 108% higher

All risks were higher for younger adults. Older adults, above age 65, were not at significant risk until BMI exceeded 35.

A study published late in 2023 provides the best early evidence that semaglutide might have a significant impact on mortality and morbidity at least for people with quite severe pre-existing cardiovascular disease.10

Scientists enrolled over 17,000 patients, all aged over 45 and with a BMI of 27 or higher. All had a prior heart attack, stroke or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Half received semaglutide and half placebo. After a mean follow-up of a little over three years, people using the drug had lost 9% of their body weight versus 1% for those on placebo. Incidence of cardiovascular death, and non- fatal heart attacks and strokes were 20% lower in those taking semaglutide, though for death alone this finding did not quite achieve statistical significance.

While this group leans strongly towards the uninsurable, this hints at the possible emergence of significant benefits, over a longer period, among those who appear more commonly in protection books.

Beware the rebound

Approximately 30% of adults in the UK, Canada and Australia are currently obese (BMI > 30) and this is nearer 40% for the United States.11

It is not difficult to see how weight loss on the level seen in the semaglutide trial could have a significant impact on mortality and health if it were sustained. However, that is the problem.

A key limitation of these drugs is that doctors currently recommend them for use for a maximum of two years due to lack of evidence relating to more sustained usage.

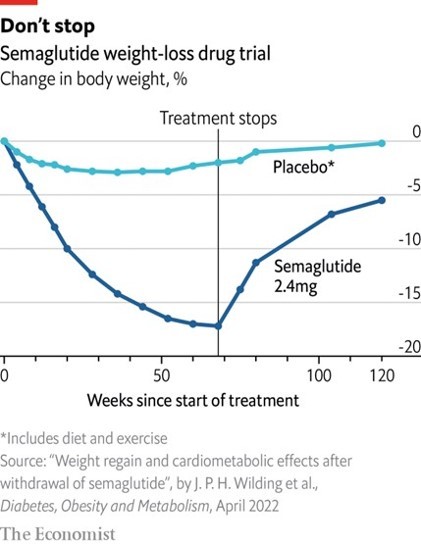

Studies show that once people stop using GLP-1 agonists, it is typical for much of the weight lost to be regained.

In the trial shown below, the average user regained around 70% of the weight lost. If this wasn’t bad enough, ‘yo-yoing’ weight can have detrimental physical impacts on the body, eventually affecting metabolism and increasing risk of diabetes and heart disease.12 It can also be psychologically devastating for some.

In any event we typically expect ‘real-world’ impacts of a drug to be somewhat smaller than those in its supporting trials. Pharmaceutical companies structure trials to maximise their chances of showing a strong positive impact for the drug which they hope to sell.

GLP-1 agonists also come with side-effects

Feelings of nausea and vomiting are reasonably common, preventing some people from engaging with the drugs for long enough to allow them to work.

All of this reduces the likely potential impact of the drugs significantly. Instead of expecting users to sustain indefinitely reductions of 15-20% of their body weight, we can perhaps expect the weight to be lost for a period of two or three years in many people. The impact of spending this period of time at a lower weight may still be beneficial, but far less than if this were maintained long-term, and potentially offset by some of the physical and psychological effects of ‘yo-yo’ dieting described above.

Underwriters should also be aware of the increasing possibility that an applicant disclosing usage of the drugs at time of application may have a significantly higher ‘natural’ weight to which they may soon return.

Weighing up industry impacts

We expect the impacts of GLP-1 agonists on mortality and morbidity will be more significant for those at highest risk, i.e. those who weigh most. This is because a higher proportion of mortality risk for this group relates to risks directly associated with weight. The benefit of using the drug will therefore reduce in line with a person’s weight.

At the other end of the scale, people who are not overweight at all can, and do, use the drugs when available. The desire to lose weight is not restricted to those with significant medical need. However, this group will likely experience negligible benefit, on balance, with minor harms offsetting possible minor benefits associated with secondary impacts on future cardiovascular health.

Currently in the UK a two-year pilot of semaglutide is underway. The numbers eligible are small (approximately 35,000 people) and therefore the impact of this pilot on the health of the population will not be material. However, semaglutide is also available privately, for example through high street chemists. The true numbers using the drug now are therefore significantly higher, and growing as availability of the drugs improves to match high demand. In addition, we can expect wider usage within healthcare settings in future, especially if the results of the ongoing trial are positive. All of this is likely to result in material, if modest, impacts on population health in the medium-term. Protection insurers can expect wider rollouts of these drugs to be broadly beneficial for in-force business, especially rated business.

We recognise the potential for a minority to lapse their policies and re-apply at lower rates, which would partially offset these gains. As for non-rated business, many people who are overweight, or low-level obese, obtain standard rates. Although impacts at the individual level would be more modest at these weights, this group is large and could still materially benefit from these drugs.

In addition, we also anticipate benefits for morbidity products, especially Critical Illness products with a broad range of cardiovascular covered conditions. No existing trial data quantifies the link between usage of drugs like semaglutide, and reductions in events such as heart attacks, but to the extent that high weight is a risk factor for covered conditions we can reasonably expect modest reductions in these conditions. Again, benefits would be largest among those whose entry weight was highest.

Conclusion

Medical science doesn’t stand still. In the short term, the way these drugs are used can, and likely will, change, as early supply issues ease and scientists learn more about long-term effects.

In the longer-term other drugs taking advantage of this mechanism might surpass the current generation, perhaps with stronger effects and more benign side-effect profiles.

Social media influencers and celebrities are encouraging use of these drugs, presenting them as a life-changing technology, typically to groups with little medical need for the drugs. This increases demand, reducing availability for those most in need, and leads to the apperance of more dangerous ‘off-brand’ versions.15

However, used properly, and with improved supply, it is true that we can expect material health impacts for many individuals who will lose significant weight. At a population level, these are reasons to temper our expectations somewhat, but the number of people affected by obesity is so large that even modest per-person benefits could have reasonably significant impacts on the health of the population at large.

However, the number of people impacted by obesity is so large that, if the drugs become widely available, even modest per person benefits could have reasonably significant impacts on the health of the population at large.

References

- Obesity (who.int)

- Mortality and life expectancy trends in the UK - The Health Foundation

- Note the two periods represented by the blue and pink bars are different lengths. Had rates stayed near constant, the pink bars would be approximately half the length of the blue ones.

- 12 Causes of Obesity - EASO

- Tirzepatide versus semaglutide for weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A value for money analysis - Azuri - 2023 - Diabetes,

- GLP-1 agonists: Diabetes drugs and weight loss - Mayo Clinic

- Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity | NEJM

- BMI as a measure of risk is well-known to be flawed as it fails to capture natural variation in people, some of whom have a higher healthy weight than others. However, it is easy to collect and measure and retains currency both in the medical and insurance worlds.

- Body mass index and all-cause mortality in a 21st century U.S. population: A National Health Interview Survey analysis - PMC (nih.gov)

- Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes | NEJM

- Obesity - Our World in Data

- Yo-Yo Dieting: The Long-Term Effects – Forbes Health

- How the new generation of weight-loss drugs work (economist.com)

- Eligibility for semaglutide use in the UK pilot requires a BMI if 35 or higher. Some people with lower BMIs (at least 30) are eligible if they also have co-morbidities. Eligibility also requires meeting criteria for enrolment in and engagement with official weight management services.

- Off-brand Ozempic and Wegovy weight- loss drugs are a bad idea, FDA says | Fortune Well

Pacific Life Re Limited (No. 825110) is registered in England and Wales and has its registered office at Tower Bridge House, St Katharine’s Way, London, E1W 1BA. Pacific Life Re Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulatory Authority in the United Kingdom (Reference Number 202620). The material contained in this booklet is for information purposes only. Pacific Life Re gives no assurance as to the completeness or accuracy of such material and accepts no responsibility for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting on the basis of such material.

©2024 Pacific Life Re Limited. All rights reserved.

Ian Collins

Vice President

See Lek Chew

R&D Actuary

Mike Wilson

Associate Vice President

Jennifer Chambers

Senior Analyst

Discover more Vital Insights

Protection

Changing regulations an area of opportunity for reinsurers

When asked what opportunities life reinsurers in Asia have, Pacific Life Re's Vasan Errakiah was quick to cite demand for insurance, changing regulations and the adoption of new technologies.

.png)

Protection

Solving the implementation puzzle of machine learning

Asia Insurance Review spoke to Pacific Life Re's Mr Ong Qian Hao and FWD Group's Ms Fiona Hermans to understand how strategic partnerships can effectively address these challenges and lead to successful outcomes.

Medical Advances

Update on COVID-19 and Long Covid

Read our update on the impact of mortality from COVID-19.

Medical Advances

Lung cancer screening, marginal gains or a game changer?

Lung cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage leading to poor prognosis for the individual. We look at how screening could have an impact.

Underwriting & Claims

From Barrier to Benefit: Rethinking the Future of Underwriting

Underwriting has been going through significant transformation over the last few years and continues to accelerate at an unprecedented pace. Traditionally seen as a barrier, there is now a growing opportunity to position underwriting as a strategic asset.

Protection

Leveraging big data insights in reinsurance

Big data analytics has been instrumental for (re)insurers aiming to boost performance, efficiency, and effectiveness.

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 2

From emerging drugs which battle obesity to a review of the effectiveness of new blood tests both to detect cancer and to help slow down Alzheimer’s, we hope these insights help keep you up to date with the latest in medical research.

Medical Advances

Vaping vs. smoking: what are the risks?

Vaping is generally considered less harmful than smoking, however longer-term risks have not had time to emerge and could prove considerable.

Medical Advances

Gut Check: the concerning rise of bowel cancer among young adults

Despite broadly improving cancer mortality, some types of the disease are increasing in incidence

Protection

Serving the Underserved

Consumer Duty has put increased focus on how much value different customers get from financial products. But how well is the protection industry serving different customer groups? Who are the most underserved groups, and what can the industry do to help serve these groups better?

Underwriting & Claims

The future of underwriting is now... are we ready?

Underwriting processes, practices and philosophies are changing with faster pace than we have ever experienced before.

Medical Advances

Tackling the obesity crisis

A new generation of drugs has now well and truly arrived aiming to improve weight loss. The drugs are heavily touted by celebrities and influencers, despite many of them having no medical need to lose weight. Obesity contributes significantly to some of the most common causes of death including heart disease and cancer, as well as affecting quality of life for millions. In this article we look at these increasingly available drugs offering hope to more people with obesity. We consider their potential to broadly improve health, and their limitations.

Medical Advances

New drug may slow down multiple sclerosis

Scientists successfully conducted early-stage trials which provide hope of a future cure for some of the most severe types of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Medical Advances

Exploring the latest medical advances in cancer detection

The world’s largest conference dedicated to the science and treatment of cancer took place in Chicago in early June. The American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting is a popular forum at which new scientific developments are often revealed.

Medical Advances

Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumour (PitNET)

A recent review by WHO resulted in reclassification of pituitary adenoma as described in the article

Medical Advances

Climate change and its impact on mortality and morbidity

In 2023 we’ve seen soaring temperatures across the globe along with devastating storms and wildfires. Why is our climate changing and what impact is it having?

Medical Advances

Vital Insights Issue 1

Welcome to our first edition of Vital Insights. Here we’ve put together a collection of articles covering some of the major issues of the day with a specific focus on how they will impact mortality and morbidity.

Medical Advances

Deep dive: Alzheimer's

Total deaths from dementias in high-income countries have almost quadrupled in the last 20 years, yet so far medical science has very few answers. This article looks at the recent emergence of the first drugs which may be able to modify the effects of this terrifying disease

Medical Advances

New Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine

COVID-19 has stolen the limelight from other respiratory viruses in recent years. However there are plenty of other common viruses which can have serious health consequences, among them Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV.

Medical Advances

An end in sight for AIDS

A new UN report reveals optimism about a possible end to the global AIDS epidemic

Medical Advances

Anti-vaccine sentiment increases risk of measles outbreaks

Vaccine technologies have continued to improve greatly in recent years. However, vaccines are little use if people refuse to use them. Here we look at the precarious position of measles, a well-known but little-understood serious condition, which is held in check in most countries only because of high vaccine uptake.

Medical Advances

Does a common sweetener cause cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of the WHO, recently classified the common sweetener aspartame as a possible cause of cancer in humans.

Protection

Building a sustainable protection market

Beneath the Surface report 2023 We explored some of the key drivers of sustainability for the protection market. We undertook consumer research which combined with our medical and underwriting expertise and our deep understanding of the market, enabled us to create this report.

.png)

Protection

Navigating the ocean of Value-Added Services

Beneath the Surface report 2022 In this report, we analyse the current VAS landscape in the UK & Irish protection markets. Look to understand the views and experiences of customers, with the aim of assessing how much value these services are really adding today. Look at what insurers say, and consider what the future might hold for the development of VAS.

.png)